Céline Sciamma

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

- DirectorCéline Sciamma

- CinematographerClaire Mathon

ILENIA MARTINI In this film, you understand how looking can become devotion, and how attention itself can become a form of closeness. Sciamma creates an intimate world in which emotions appear gradually through small gestures and pauses. It’s a calm film that draws you in, and the director’s patience with the storytelling is something I admire. Some connections mark us because they can’t be kept, and this film is a testament to that.

The story behind Portrait of a Lady on Fire

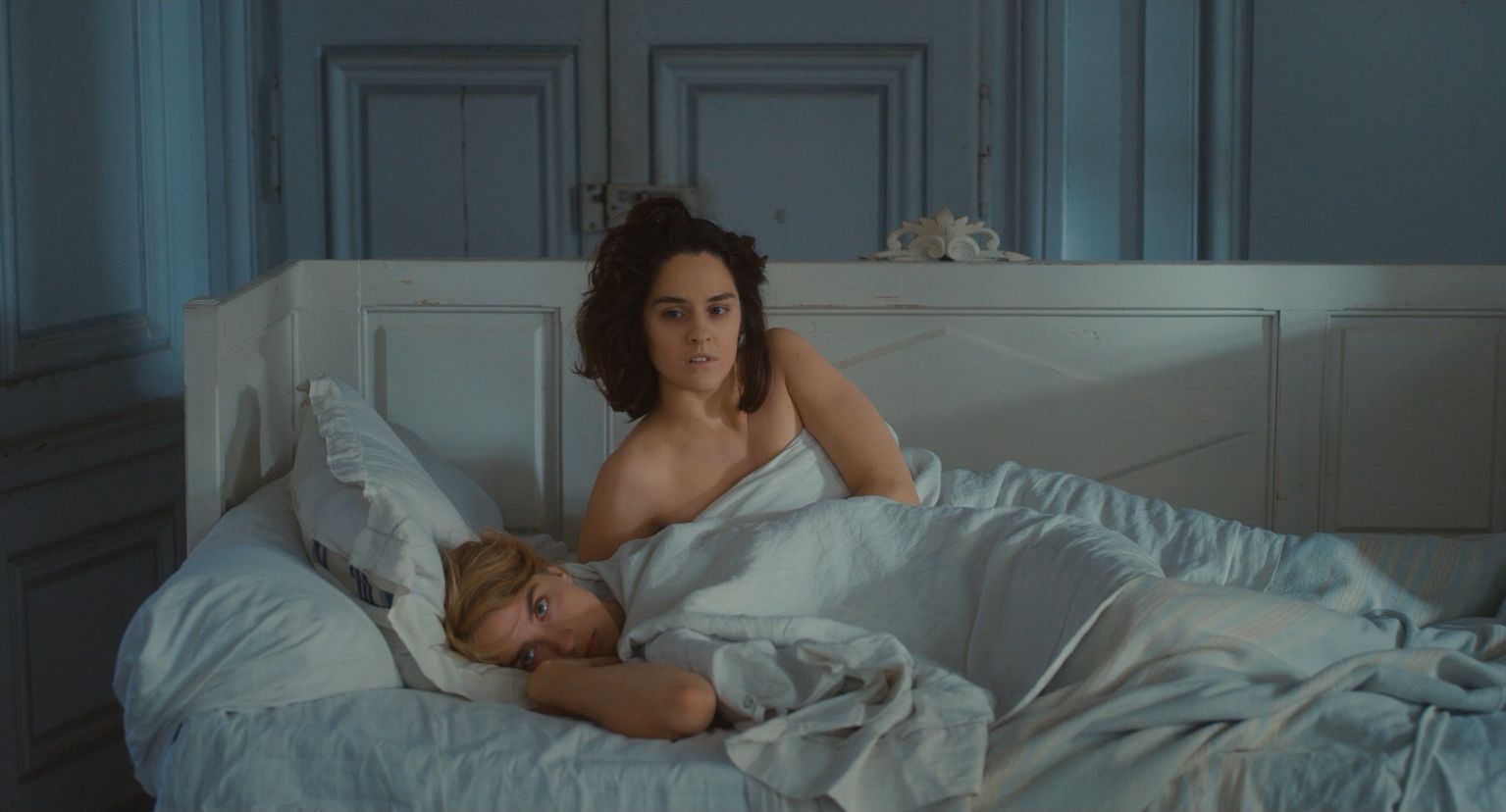

Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019) unfolds like a memory you return to long after it has ended - precise, luminous, and quietly devastating. Set in the late eighteenth century, the film tells the story of Marianne, a painter commissioned to secretly paint Héloïse, a young woman destined for a marriage she refuses. What begins as an act of observation becomes an intimate exchange, transforming the gaze itself into a form of love.

Sciamma, one of contemporary French cinema’s most distinctive voices, wrote the film as a deliberate refusal of tragedy traditionally imposed on queer stories. Rather than punishment or spectacle, the lovers are separated by time, social order, and inevitability. Love is not denied; it is simply finite. Sciamma has described the film as a meditation on memory - how an intense but brief love can endure through remembrance rather than possession. This idea is echoed in the film’s dialogue around the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, which becomes the emotional architecture of its ending.

The tonality

The film’s visual language reinforces this philosophy. Shot by cinematographer Claire Mathon, the images are composed with painterly restraint: soft natural light, candlelit interiors, and carefully balanced frames that recall classical portraiture without mimicking it. Mathon’s camera lingers on faces rather than bodies, allowing desire to emerge through glances, posture, and breath. The absence of intrusive camera movement creates a sense of equality between subject and viewer, aligning the audience with Marianne’s act of looking - and learning how to see.

Men are largely absent from the frame, a conscious decision by Sciamma to explore what happens when women exist beyond surveillance. In this rare cinematic space, looking becomes reciprocal, consensual, and transformative. Even the paintings in the film - created in real time by artist Hélène Delmaire - mirror this process, evolving as Marianne’s understanding of Héloïse deepens.

The Fire That Remains

Fire, a recurring image, is not destructive here but mnemonic. It signifies moments that burn briefly yet leave permanent traces. By the time the film reaches its final sequence - an unforgettable act of silent witnessing - Portrait of a Lady on Fire has fully revealed itself as a film about what remains after love ends: the image, the sound, the memory that continues to glow.