Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck

The Lives of Others

- DirectorFlorian Henckel von Donnersmarck

- CinematographerHagen Bogdanski

SALOMON LIGTHELM What stays with me is how a man conditioned to surveillance and control finds empathy through art. It’s intimate, restrained, and deeply moving. It’s about how art changes us, even when we don’t expect it to.

The film

The Lives of Others (German: Das Leben der Anderen, 2006) is a German drama written and directed by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, marking his feature film debut. Set in 1984 East Germany, the story follows Stasi Captain Gerd Wiesler, tasked with surveilling celebrated playwright Georg Dreyman and his lover, actress Christa-Maria Sieland. What begins as a routine assignment evolves into an intimate exploration of loyalty, conscience, and moral choice. Wiesler becomes increasingly sympathetic to the couple, subtly intervening to protect them while navigating the oppressive machinery of the state.

The narrative reflects Henckel von Donnersmarck’s own fascination with East Germany, shaped by visits to family there and a sense of the pervasive fear under Stasi surveillance. Released 17 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the film was the first serious East German drama following comedies like Good Bye, Lenin! and was praised for its authentic tone despite some dramatization of historical events.

The legacy

The Lives of Others received international acclaim, winning the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film, seven Deutscher Filmpreis awards including Best Film and Best Actor, the BAFTA for Best Film Not in the English Language, and the European Film Award for Best Film.

Critics praised the film for balancing tension and emotional depth: Roger Ebert described it as “a powerful but quiet film, constructed of hidden thoughts and secret desires,” while Time magazine called it “a poignant, unsettling thriller.” Its exploration of morality, free will, and the fragility of human dignity continues to resonate, earning it a lasting place in both German and global cinema. The film’s subtle layering of narrative, historical insight, and visual storytelling makes it a compelling study of surveillance, ethics, and the human capacity for empathy even under oppressive regimes.

The Cinematography

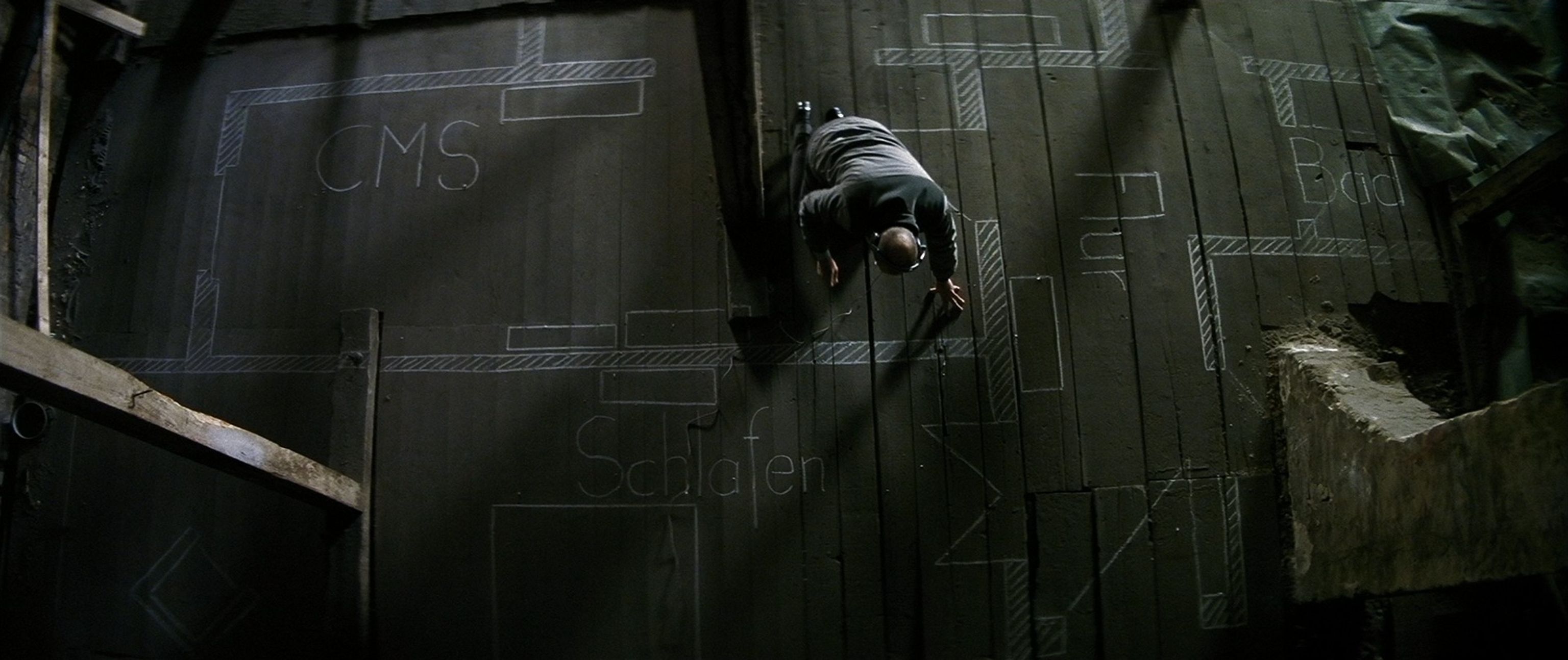

Collaborating with cinematographer Hagen Bogdanski, Henckel von Donnersmarck crafted a Brechtian, grey-toned visual palette that emphasizes the dim, interior world of East Berlin. The camera lingers on intimate spaces, private gestures, and small details, creating tension through subtle observation rather than conventional action. The score and the role of music, particularly Beethoven’s Appassionata, become central narrative devices, mirroring Wiesler’s internal transformation and moral awakening.

The film is defined by its meticulous attention to detail: repeated visual motifs, careful framing, and an emphasis on sound and silence heighten the emotional stakes and immerse viewers in the moral dilemmas of everyday life under totalitarianism.